Drone image of the three researchers looking for microbes near the Svartisen glacier. Photo: Alex Détain

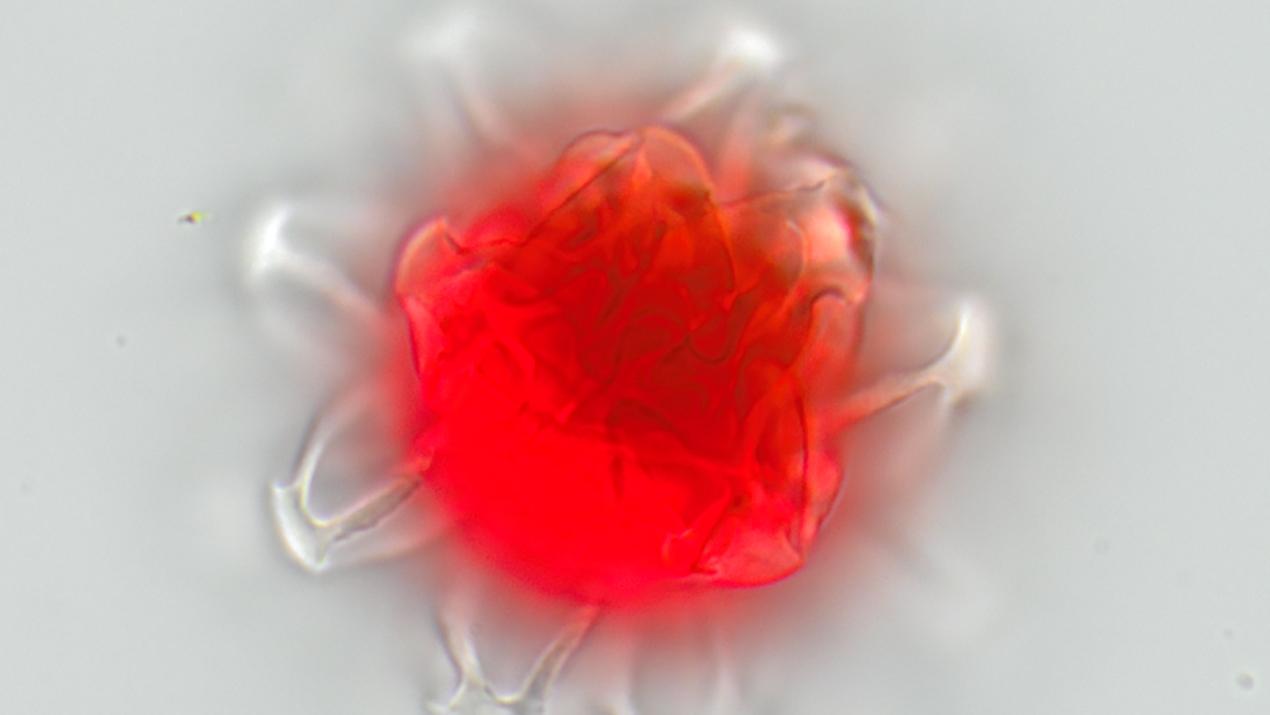

It is found all over the world and is often called red snow or watermelon snow, as it appears as a reddish veil across the surface of snow during spring and summer.

The microalga Sanguina nivaloides and its relatives belong to a group of freshwater algae that have adapted to some of the harshest habitats known. They live in snow in high mountains and polar regions, at temperatures near freezing and with extremely limited access to nutrients.

When summer arrives, they are found on the snow surface, where they are exposed to extremely high doses of light and ultraviolet radiation.

Scientists don’t fully understand how these blooms form, but it is thought that the snowmelt dynamics and perhaps the swimming activity of individual cells might contribute to the appearance and intensity of blooms.

Now, researchers at Nord University have succeeded in cultivating snow algae in the laboratory.

“Snow algae are among the few organisms performing photosynthesis in these areas, and they are an important part of the microbial food web in alpine and polar ecosystems,” says Chris Hulatt.

He is an associate professor at Nord University and studies how microalgae can be utilized in biotechnology.

Together with researchers Alexandre Détain and Hirono Suzuki, he is now helping to shed light on how this peculiar little microalga has adapted to life in snow and freezing conditions.

It all started by coincidence, Suzuki explains:

“We had been in Trondheim to pick up a car and were heading north when I convinced Chris to stop by Glomfjord.”

She wanted to see the dam at the Glomfjord power station — 125 meters high and 365 meters wide. It dams up Lake Storglomvatn, part of the Saltfjellet–Svartisen National Park. When the researchers reached the snow-covered area, they quickly noticed that in many places, the snow was tinged red.

“It was the first time we had seen snow algae in Northern Norway. So we scooped up some samples in our lunchbox and brought them back to the lab to make sure it was what we thought.”

Interest in microalgae that live in snow has increased significantly in recent years in the scientific community. When the algae form large carpets on the snow, they affect the melting process: sunlight is not reflected as effectively as when the snow is white.

This means the snow absorbs more heat and melts faster. That’s bad news for glaciers—and the effects may interact with global warming.

“At our lab, we have already done a lot of research on cold-adapted microorganisms, as they are very efficient at producing certain proteins and omega-3 fatty acids that can be used, for instance, in fish feed. Now we wanted to study the physiological and biological aspects of these snow algae,” Suzuki says.

One of the great mysteries of these algae is how they reproduce to form large colourful blooms.

“When we find the algae in the snow, they are in the form of small cysts filled with the red pigment astaxanthin, which protects them from high light exposure. A cyst is a kind of dormant stage, where it's hard to imagine they could reproduce. So the theory is that they have a stage where they are not cysts, but green algal cells that can reproduce and swim. But this has yet to be studied properly,” Suzuki explains.

When grown in the lab however, the tiny single-celled algae are green and equipped with cilia (small hair-like structures) that allow them to swim. The researchers in Bodø have now measured the swimming abilities of snow algae under the microscope by filming them.

It turns out the snow algae swim better at temperatures just above freezing than they do at higher temperatures. It shouldn't get too warm—at 25–30 degrees Celsius, their swimming stops.

“These algae can survive anywhere there’s just a little bit of water for them to move in. In snow, even a thin film of water is enough for them to swim. We see that they can move toward sunlight, but they’re also capable of avoiding light if it becomes too intense,” explains Détain.

The algae are able to perceive light, temperature, and nutrient concentrations.

“They have a range of different sensors they use to guide their movement. What’s astonishing is that they’re able to do this at very low temperatures.”

The researchers believe the ability to swim is fundamental to the algae’s life strategies.

“Green algae like these rely on their swimming life stages during growth, photosynthesis and reproduction. Swimming allows the entire population of algae to move relatively large distances to find adequate conditions and multiply. That can be a distance of a few centimeters to a meter or more, which they manage to cover by swimming against gravity,” says Détain.

Now the question is how snow algae will be affected by climate warming.

“These algae are vulnerable to high temperatures, and we expect summers to become both longer and warmer in the future, with changes in snow extent and melting patterns. The Arctic is especially sensitive to warming and is already undergoing major changes. Maybe they’ll disappear—or maybe they’ll adapt. We don’t know yet,” says Hirono.